A frequent refrain amongst non-mainstream economists has been that economics education should be “pluralist”: it should introduce students to many schools of economic thought, and not just Neoclassical economics. This is portrayed by its advocates as a noble objective—to cite the website “Promoting Economic Pluralism”:

The term pluralism is generally used to contrast with so called ‘mainstream’ economics teaching which generally only focusses on one school of economic thought called neo-classical economics.

This has a number of key assumptions that are central to its approach such as economic agents seeking to maximise their individual happiness and markets tending towards equilibrium and generally leading to efficient outcomes.

Pluralism in contrast recognises and teaches a range of different approaches to understanding the economy and its interaction with the wider social and environmental systems in an interactive, reflective and engaging manner.

However, pluralism is really a concession to the fact that Neoclassical economics dominates the academic teaching of economics, is hostile to any other approach, holds the purse-strings for research funding, and acts as a gatekeeper against alternative paradigms at all but the most lowly- ranked of universities. The only way for non-Neoclassical teaching and research to survive at Universities is therefore to plead for pluralism, which translates as asking Neoclassical departments to not persecute their non-Neoclassical staff, and to tolerate some courses being not strictly Neoclassical in nature.

This should not be happening, because Neoclassical economics should already belong to the history of economic thought, as a failed paradigm every bit as wrong about the economy as Ptolemaic Astronomy was about the universe. If economics responded to paradigmatic anomalies as physical sciences do, then Neoclassical economics would have died by the early 1970s, and a new paradigm would have replaced it.

Instead, because the generational change dynamic of a physical science does not apply to social sciences, economics avoided a scientific revolution, despite the numerous anomalies it had accumulated by then.

A partial list of the anomalies that had mounted up against it by the early 1970s include:

- The Perron-Frobenius Theorem, developed in the early 1900s as an exercise in pure mathematics,165 which coincidentally proved that Walras’s tatonnement process cannot reach equilibrium (Jorgenson 19602, 19613, 19634; McManus 19635; Blatt 19836);

- The Great Depression, which a self-equilibrating system would not have experienced (Fisher 19337);

- The empirical fact that real world firms have constant or decreasing marginal cost curves, thus invalidating the concept of the supply curve (Andrews 19498);

- The Cambridge Controversies, which showed that the marginal productivity theory of income distribution could not be correct (Sraffa 19609; Samuelson 196610; Garegnani 197011; Harcourt 197212); and

- The so-called “Sonnenschein Mantel Debreu Theorem”, first discovered by Gorman in 1953 and Samuelson in 1956, which proves that a downward-sloping market demand curve cannot be derived from individuals with downward-sloping individual demand curves (Gorman 195313; Samuelson 195614; Sonnenschein 197215).

I could go on, but those will suffice. These and myriad other anomalies should have led to a scientific crisis and ultimately, a scientific revolution. But not only did Neoclassical economics not experience a crisis, it became even more extreme in its devotion to its original foundations, in sheer ignorance that these foundations had been proven to be unsound.

The fact that Paul Samuelson himself conceded defeat in the Cambridge Controversies1To remind you, the closing paragraph of Samuelson’s final engagement with the Cambridge Debate, “A Summing Up”, was “If all this causes headaches for those nostalgic for the old-time parables of neoclassical writing, we must remind ourselves that scholars are not born to live an easy existence. We must respect, and appraise, the facts of life”. (Samuelson 1966, p, 583, see note 10 for the complete reference). was forgotten, and every one of those intellectual failures listed above led not to the soul-searching that occurs in a physical science, but to a canonical dogma.

The Perron-Frobenius theorem showed Walras’ equilibrium is mathematically unstable? Then let’s just assume stability! (see McManus 19635; Jorgenson 19602, 19613, 19634) Equilibrium, having failed logically, was converted from the necessary but temporary salve that Jevons, Marshall and Clark perceived it to be, prior to the development economic dynamics, into a defining aspect both of what economists think is a science (Lazear 200016), and of its normative perceptions of capitalism.

I am not saying that Neoclassical economists did this as a conscious strategy—the majority of them are unaware that these anomalies even exist17. This defence of the paradigm when an anomaly is identified is also standard behaviour by scientists who are supporters of a paradigm when it is first rend asunder by a fundamental anomaly.

For example, by developing the telescope, Galileo gave birth to the paradigm of a Sun-centric solar system which we now name after Copernicus, because the telescope provided conclusive proof that the Ptolemaic Earth-centric paradigm was false. It revealed craters on the Moon, which showed, not only that “Heavenly Bodies” weren’t perfect spheres, but also that there also must have been collisions between celestial objects in the past. It showed that a core principle of Ptolemy’s model, that everything orbited the Earth, was false, because there were clearly Moons orbiting Jupiter.

And how did Galileo’s contemporaries react? We all know of his treatment by the Catholic Church, but more telling was the refusal of Ptolemaic astronomers to use the telescope in the first place:

"My dear Kepler," wrote Galileo to his friend, the German astronomer, "what would you say of the learned here, who, replete with the pertinacity of the asp, have steadfastly refused to cast a glance through the telescope? Shall we laugh, or shall we cry?"18

(emphasis added)

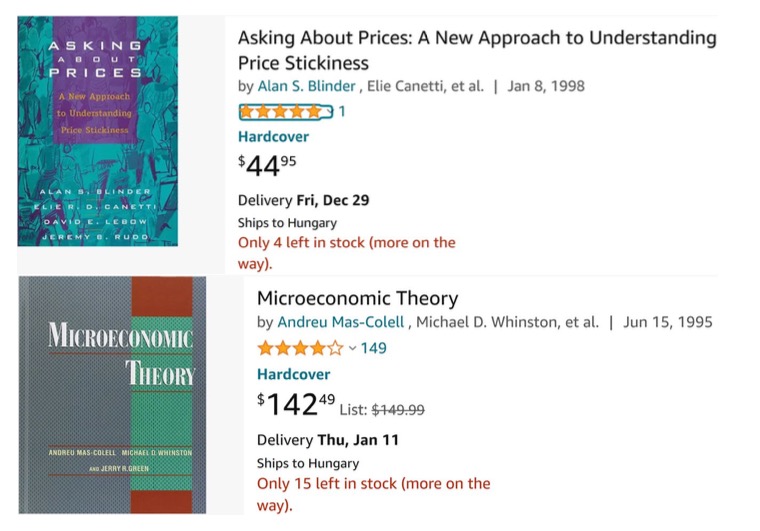

A similar behaviour pervades Neoclassical economics. I footnoted earlier that Alan Blinder’s book "Asking About Prices"19 —which found inter alia that the vast majority of America’s GDP is produced under conditions of constant or falling marginal coat—has had only one review on Amazon after a quarter century of existence, while Mas-Colell’s Microeconomic Theory20, a core Neoclassical text for PhD programs, has almost 150.

To further illustrate that Neoclassicals don’t read what they don’t want to know, that one review was written by me.

A more prominent example is the Neoclassical treatment of the Central Bank papers "Money creation in the modern economy" e "The role of banks, non-banks and the central bank in the money creation process" that categorically rejected both the “Money Multiplier” and “Loanable Funds” models of money creation. Not only did Neoclassical economists trivialise these papers, they also completely ignored them when they awarded the 2022 “Nobel” Prize to Bernanke, by not even citing them in the so-called “Scientific Background” paper for the Prize.

A school of thought that will not even admit that anomalies exist is one that has clearly failed. But Neoclassical economics staggers on because, unlike a true science, there is no process of generational change that can bury a failed paradigm along with the corpses of its adherents.

Consequently, academic economists who have taken these anomalies seriously and have abandoned the Neoclassical school, still find themselves dominated by Neoclassical economists, both at individual universities and in the profession as a whole. Their situation is akin to Galileo, who was forced to recant the concept that the Earth moves to avoid execution by the Inquisition. Economists calling for Pluralism are, consciously or otherwise, muttering “And yet it moves” under their breath, while being forced to pretend otherwise to avoid being driven out of Universities altogether.

Pluralism is thus a survival tactic by non-mainstream economists, rather than a call to “let a thousand flowers bloom”. In reality, there is no place in a scientific economics for as flawed a paradigm as Neoclassical economics, but economics cannot be relied upon to reform itself and reject this failed paradigm via a scientific revolution. The only way forward that I can see is for real scientists to realise how unscientific the Neoclassical paradigm is, and to develop an alternative themselves, building on the foundations laid predominantly by economists from the realism-oriented Post-Keynesian tradition.

There are some scientists who are already aware of this need, such as Ole Peters (Peters and Gell-Mann 2016; Peters 2019; Peters and Adamou 202221), who has started to develop what he calls Ergodicity Economics. Many more will be motivated to develop an alternative when they realise, as a few have already, that the appallingly bad work by Neoclassical climate change economists is a major reason why humanity has done so little to address global warming:

It has only today percolated into my ignorant consciousness that the reason governments are doing next to nothing on climate is bad economics. Siloed economics that knows nothing about climate impacts on human civilisation. Economics papers reviewed only by fellow economists.

— Prof Nick Cowern (@NickCowern) October 17, 2023

***

This article is an unpublished excerpt from Steve Keen's forecoming book, “Rebuilding Economics from the Top Down", to be released by the Budapest Centre for Long-Term Sustainability and Pallas Athene Publishing House.